Under electric current

The old, disturbing images have left a lasting impression on popular culture. We only have to cast our minds back to One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975), where psychiatric patients are subjected to electric impulses and come out of the procedure looking like a shadow of their former selves. The whole thing seems more like a form of torture than an actual medical treatment. This negative image continues to plague electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) to this day, and Professor Ronny Redlich from the Institute of Psychology is keen to change our perception: “ECT has become a scientifically undisputed means of treating certain patients, such as those with major depressive disorder, and can achieve very positive results”. In a project funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG), he is working with his team to find out exactly what happens in the brain during the procedure. He also wants to know why this form of therapy works well for some but less so for others.

The answers to these questions are not only of great medical importance; they are also of interest to the general public. After all, depression is one of the most common illnesses of all. Around the world, more years of life are lost to depression than to cancer or cardiovascular disease (taking into account not only the deaths, but also the years in which sufferers are no longer able to participate in everyday life due to their illness). So there is an urgent need for effective therapies.

The idea of using electricity is by no means new; as early as the 1930s, doctors began sending electrical impulses through patients’ brains to treat depression and other mental disorders. “But it was still fairly experimental and brutal back then”, says Redlich. The electrical current flowed through the patients’ entire body, triggering convulsions similar to an epileptic fit. In order to avoid injury, they were given something to bite on and were held down by six or seven orderlies.

“That’s obviously unacceptable by today’s standards”, says the psychologist. However, the modern face of ECT is completely different to what happened in the early years. On the one hand, patients are injected with a muscle relaxant before the treatment, which ensures that a seizure is only induced in the part of the body that is actually targeted: the brain. On the other hand, the whole procedure is carried out under general anaesthetic, which wears off after 15 minutes. During this time, precise electrical impulses are administered via electrodes placed on the head of patients, who don’t feel anything at all. When they come round after the procedure, they often feel tired and listless; however, this is mainly due to the anaesthetic. Some also report transient memory loss in the days following ECT.

Apart from those complaints, however, the therapy has only a few side effects – especially in comparison to a number of psychotropic drugs. And it is a promising option for people who have not responded to other treatments.

“Most depression patients can be managed fairly well with psychotherapy, medication or a combination of both”, says Ronny Redlich. However, his experience as a therapist has also shown him the other side of the story; some patients seem utterly helpless after moving from one practice to another. Around 60 to 70 percent of those patients feel significantly better after ECT.

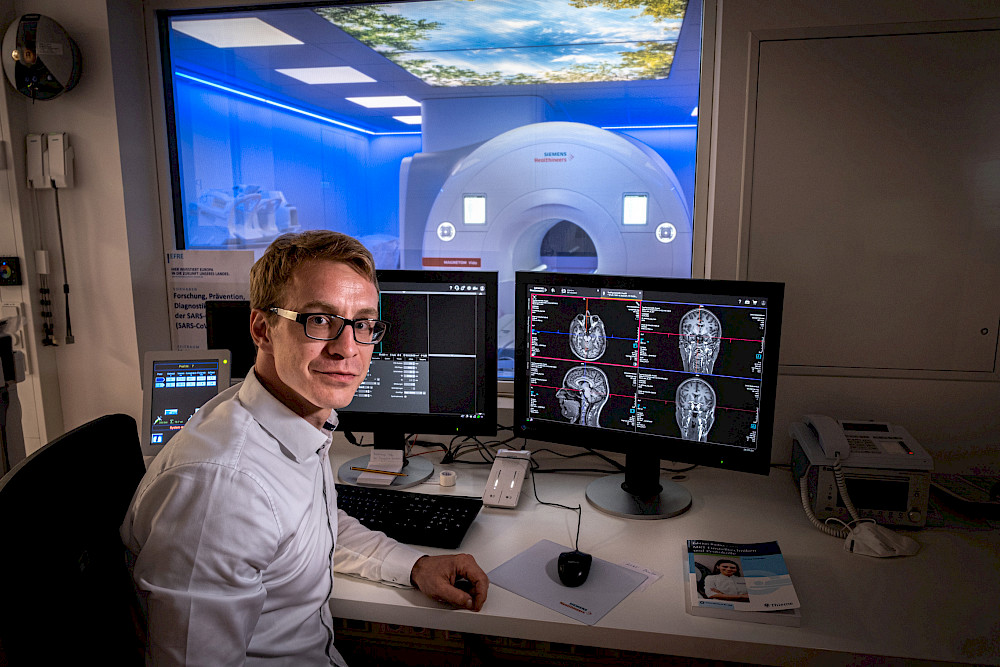

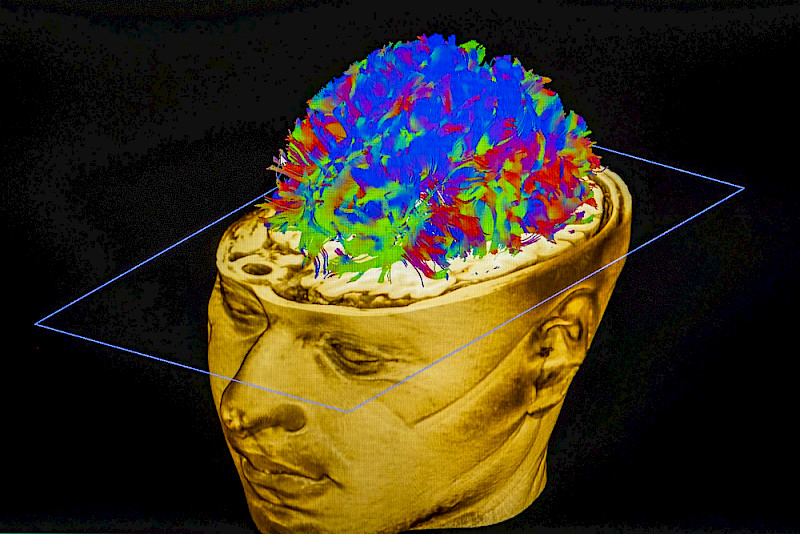

However, we are yet to discover exactly what causes the improvement. At the same time, a deeper understanding of the therapy would help us assess its possibilities and limits. That’s why a team of experts have been investigating this question for the past ten years using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). They have been using high-tech devices to take high-resolution images of the brain before and after the treatment, revealing striking differences particularly in the area of the hippocampus, which plays an important role in learning and memory. Hippocampal grey matter, which mainly consists of neuronal cell bodies, is often reduced in people with depression, but ECT frequently leads to a massive increase in grey matter volume.

But does the therapy actually lead to the formation of new neurons in that part of the brain? Or are the existing neurons just better connected? What is the role of chemical messengers that transmit signals from one neuron to the next? All these mysteries remain unsolved. Ronny Redlich and his team want to use the data obtained in the DFG-funded project to shed more light onto these issues. To do this, they are producing images of patients’ brains before undergoing ECT, immediately after the procedure, and after six and twelve months. In doing so, they not only want to gain a better understanding of how the therapy works; they also want to see who responds well to the treatment and who doesn’t.

There must be some subtle differences between the brains of each group. “But these aren’t visible to the naked eye on the MRI images”, says Redlich. That’s why he and his team are using automatic image recognition and artificial intelligence, feeding the data from their MRI studies into computer programmes. “With the help of algorithms, the computer learns how strongly each patient has benefited from the electrical impulses”, explains the psychologist. In this way, the computer gets an increasingly precise impression of the tiny peculiarities in the brain that determine the success of the therapy. And based on this information, the computer will then ideally be able to predict how well a new patient will respond to the electrical impulses. “Our predictions are already 80 percent accurate”, reports Redlich. And that can save a lot of time and effort for everyone concerned.

After all, ECT is a fairly complicated procedure in which patients have to undergo general anaesthesia two to three times a week for four to six weeks, and so the chance of success should be relatively high for them to initiate such a treatment plan. Otherwise, it might be better to try a different psychotherapeutic approach or a different drug instead.

Ronny Redlich’s team is also taking a closer look at these alternative treatment methods, the way they work and their chances of success. “There is no approach that works equally well on all patients”, says the researcher. That’s why he wants to give doctors and therapists the opportunity to develop a course of therapy tailored to each individual patient before they begin their treatment. Everyone should get the best combination of measures that promise the best success in their specific case. In other words, the treatments should be as unique as the patients themselves. According to Ronny Redlich, that could even be reality in five to ten years.