The memory of a city

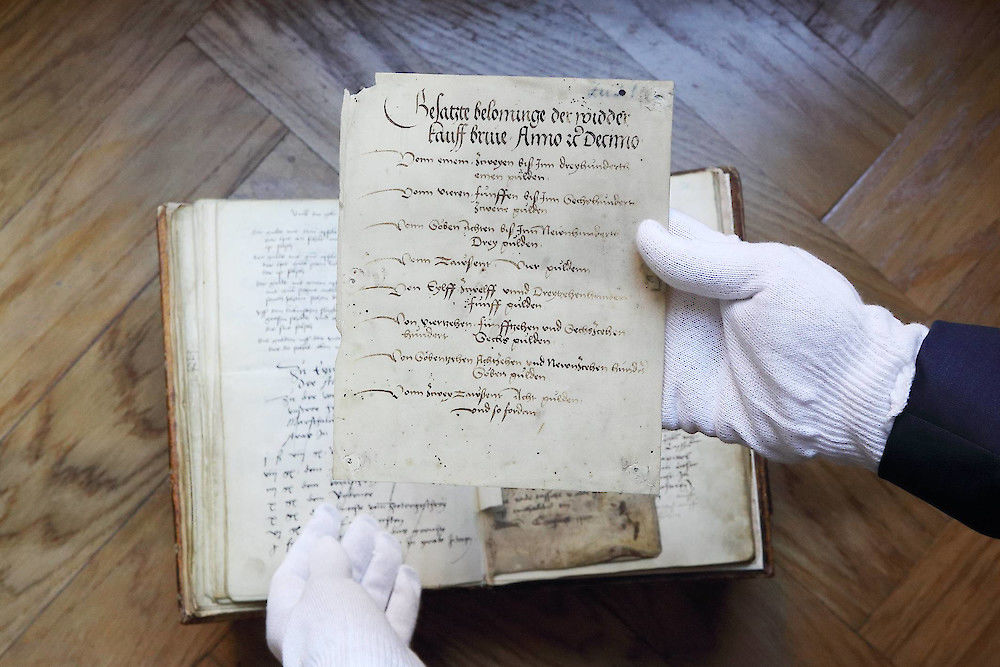

They were probably salters who were late in paying their taxes. The municipal “Kämmereibuch” (finance department book), passed down through Halle’s city archives, contains an ordinance from 1517 that was issued by managing official Hans von Peck. It states that those who have not paid their taxes to the council within 14 days of the 25th of January will be expelled from the city. Order must be kept.

City books were the backbone of municipal administration in the Middle Ages and early modern times and it’s hard to get a more vibrant glimpse of life in a Mediaeval city. A city book, liber civitatis in Latin, contains all of a city’s administrative and legal matters. The codices are one of the most important sources for historians, containing lists of council members, privileges, regulations, legal decisions, bills, tax evaders and much more.

“The city books enable us to research the phenomena of governance and administration more in-depth,” says Professor Andreas Ranft, a historian at the University of Halle. They not only allow the entire administrative history of a city to be reproduced; cultural and art historians, as well as specialists in German studies, are able to arrange their sources according to municipal contexts – wages, prices, city council decisions, and written records, sources which have rarely if ever been noticed.

In truth, city books have been studied to a lesser extent because their locations are widely scattered. They are sometimes inaccessible and it is hard to get an overview of them in their entirety. The working group led by Andreas Ranft and project coordinator Dr Christian Speer hopes to unearth these historic treasures. First the team has to do some groundwork. This is so important to the DFG that it is providing four million euros over twelve years from its long-term programme. This is something that rarely happens.

Online directory of centuries-old sources

The large-scale project kicked off in February of this year. The aim is to nationally record all of the surviving city books and to systematically prepare them to be accessed by research. “The main goal is to set up a complete database which would help locate city books from all over Germany and beyond,” explains Ranft. The researchers are building upon a pilot project in which an already existing city book directory – compiled in the GDR in the 1980s – has been revised, entered into the database and annotated. The database, found at www.stadtbuecher.de, can already be directly accessed. An initial offering that is being noticed: “We are registering a rising number of hits from around the world,” says Ranft.

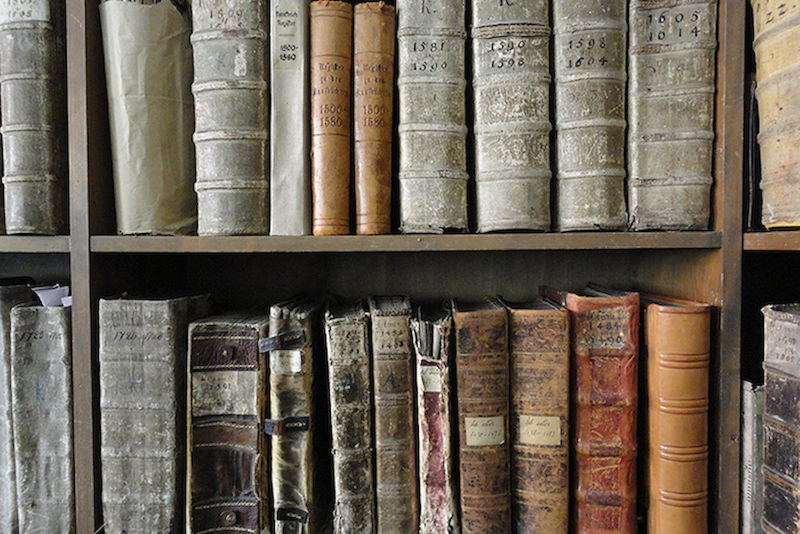

Halle’s city books are also listed in the database. After all, the city’s archives are home to 424 books from various centuries. A particularly old copy is a “Kämmereibuch” whose first entry dates back to 1451. Notes about the appearance of a comet in the sky have been recorded in it as well as the fees for gravediggers and for the disposal of waste. One entry from 1462 is overwritten with the words: “Den pful und unflot sal man nicht uff die gassen schoten” – Refuse shall not be disposed of on the street. “These kinds of entries quickly give us very vivid images about what life was like during that time,” says Ranft.

The historians frequently visit smaller communities to view inventories. They find that not all of the documents have been stored in an ideal way. For example, city book expert Christian Speer discovered historical sources in a small Central German town which contained fragments of a city book. They had been stored for decades in the town hall tower beneath embrasures. Although packed in cardboard boxes, the storage conditions were not ideal and cold, dust and humidity had already begun afflicting them.

In the coming years the historians want to work their way from northern to southern Germany laying the groundwork for the project. As part of an initial three-year project, two PhD students will work through the northern German states including Pomerania and Silesia – since the project will also include large swathes of 13th to the 18th century German-speaking territory located east of the Oder and Neisse rivers. “The goal is to record different city book landscapes, as there are different city book traditions and quite significant differences in the way municipal administration was practiced,” Ranft explains.

The town clerk as a key person

These differences are also reflected in the figure of the town clerk who played a key role as the municipality’s highest administrative official. He was highly educated, elected by the city councilmen and usually remained in office for many years. “It was a lucrative post that brought with it high standing and influence,” says Ranft, adding “He was the centre of operations and quickly gained the knowledge that every municipal council relied on.”

The project will examine the precise role of the town clerk within the network of a Mediaeval municipality and try to understand the kind of man who held such an office. One of Ranft’s PhD students is already working on this topic. Analytical studies – master’s theses, PhD dissertations and habilitations will examine the question of genesis, practice, differentiation, change and structure of municipal administration in the Middle Ages and the early modern period. They make up key components of the project along with the expansion of the database.

Now, to get back to the small communities. In contrast to the large cities, city books often lay dormant in the archives, overlooked and untouched. This is precisely what makes them so interesting for researchers. In many cases they are without gaps and document a “frozen situation,” as Ranft observes. The communities were already located off the beaten track during the Middle Ages and later were never very strategically placed. “They were situated far from major trade and traffic routes. A positive effect of this disadvantage: they were often left unscathed by major wars,” Christian Speer adds. And this has a crucial impact on the number and type of records; no war means fewer fires. For example, Christian Speer was able to access 6,000 city books in the East German town of Görlitz, which was often left unscathed by war. In contrast: “Only two or three city books survived in many cities.”

Some archives in larger cities even destroyed their old city books at regular intervals. This process was called “pulping”. In the 19th century, paper codex was sold as scrap paper or the parchment of old city books was cooked into glue – outrageous according to today’s standards and something that can never be undone. That is one more reason why the unutilised sources need to be made accessible. “Mediaeval cities are the nucleus of today’s communities and structures. Understanding them means becoming conscious of how important functional self-governance is for the community, which relied on the commitment and willingness of its citizens,” says Andreas Ranft.