Data tells history

What happens to the data at the end of a research project or when a scientist who used to work with it leaves the university or retires? “In the past this data was sometimes just lost,” says Dr Katrin Moeller. She should know since, when she became the head of the newly established Historical Data Centre at Martin Luther University in 2008, her aim was to prevent this from happening in the future. The data centre processes, supplies and evaluates mainly historical sources.

Moeller is aware of the importance of her job not only by the fact that colleagues will suddenly appear with large old discs and ask whether she can access the data on them, but also by the fact that every master’s student at the Institute of History has attended a consultation with her. She explains to them the basics of how datasets are created and documented, as well as how these can be made available later on for use in research. At the same time, she helps her colleagues publish their data and is currently developing a variety of research data servers for this purpose.

Students and staff members at the Institute of History also need to relearn how to handle data in the digital age. Several things have been done to make this process easier. “When we overhauled our master’s programme we added a consultation session on data management that is a compulsory part of the master’s thesis module. This will probably go into effect in winter semester 2016/2017,” says the historian. The bachelor’s programme already contains a lecture on using digital methods in the humanities. While the lecture provides more a theoretical framework, the consultation’s aim is to answer students’ practical and individual questions about conducting research for their master’s thesis.

In the past, students and scientists frequently didn’t approach the head of the Historical Data Centre until the end of their work, when they had concrete questions about analysing the data. Often they realised that the way in which they recorded and structured their data made it impossible to analyse or that the data could only be analysed after spending a lot of time and effort to put it in the right format. The compulsory consultation session will mean that basic rules on creating databases or spreadsheets will be taken into account at the start of the project.

Crunching data in order to utilise it

One good example of this is the so-called atomisation of data. This means that only one piece of information can be contained in every variable or spreadsheet column. Street name, house number, postcode and city are to be recorded as four individual pieces of information. It’s easy enough to merge the information later on - separating it, though, can be difficult. “Hidden” information also has to be recorded. For example, when names are recorded, people’s gender is also revealed. However, this has to be recorded separately if you later want to use a name to analyse gender as a category.

Moeller’s main objective is to make data available for use over the long term and to preserve it. It can’t just be left to chance, since historical datasets from research projects are expensive to produce. As a comparison: the lion’s share, in other words 80 per cent, of the work on a research project involves processing sources. The remaining 20 per cent of the time is used to analyse and publish the findings. To some degree, this is disproportionate says Katrin Moeller.

At the same time it also shows how urgent it is to archive such data in the future. This is currently a hot topic in science. The catch phrase is “open access”. “Naturally it will be good to have research data accessible to the general public in the future,” Katrin Moeller believes. Many people imagine huge anonymous databases that anyone can use. However, this scenario produces questions which, so far, no one has been able to answer. For example, how can and should scientific achievement be measured in the absence of any authorship of data.

Students digitalise historical sources

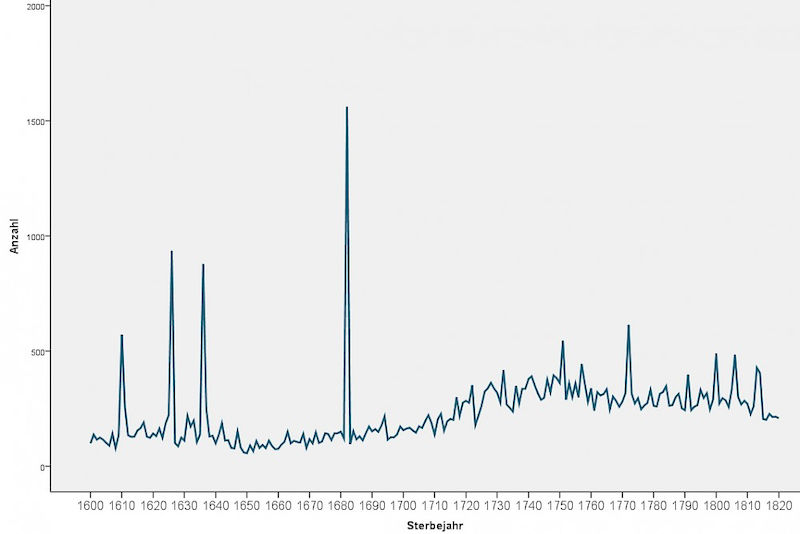

The effort it takes to conduct research is revealed by one real-life example. It took three years, for instance, for Katrin Moeller and her student assistants to digitalise and transcribe the historical records on deaths, baptisms and marriages in the parish of the Church of Our Lady in Halle from 1670 to 1820.

What initially sounds trivial was a difficult and tedious process. First the countless number of pages from the registers had to be read and recorded individually. To accomplish this, the students involved in the project first had to learn Kurrent, an old type of German handwriting, before they could even make out the handwritten entries.

In the next step all of the people listed in the registries received an ID number. This process is called “record linkage” and it ensures that everyone who appears more than once can be reliably identified again.

Finally, the historian feels it’s also her task at the data centre to tell people about new digital methods. She has acquired funding to recruit women for working digitally in research and teaching. In multiple workshops entitled “Frauenschlaue Datenpower” [Female-Clever Data Power] she will soon teach women how to analyse and manage research data. Says Moeller: “Women often think that they are less capable of using computer technology. From my own teaching experience I know that this is false. That is why I want to help reduce their trepidation.”

Contact: Dr. Katrin Moeller

Chair for Social and Economic History

Historical Data Centre of Saxony-Anhalt

Phone: 0345 5524286

Send an e-mail